The Ilokano have one of the richest weaving practices in the Philippines. Characterized by their vivid colors and precisely woven patterns, their garments and textiles are some of the most well known in the Philippines. In the barangay of Sabangan in the Ilokano municipality of Santiago, a proud community headed by Corazon Agosto continues to practice weaving traditions past down from generations of Ilokano weavers.

Corazon, also known as Manang Cora or “Coring,” began weaving in 1963. All her weaving knowledge was passed down from her mother, which Corazon eventually passed on to her own daughters along with the other female weavers she works with. It was in 1990 that the Sabangan weaving industry experienced an economic boost when Nikki Coseteng, a former Philippine senator who had a passion for local weaves, saw the works of Corazon and brought them to a wider market. This led to the Sabangan weavers partnering with the Itneg/Tingguian, and Corazon continues to use their weaving motifs in her products today.

Corazon describes her weaving practice as tawid-tawid, from the Filipino word tawid, meaning “to cross.” Like many traditional Philippine weaving practitioners, her process is laborious and technical. First, she readies her loom by placing her warp threads vertically across the structure. This allows her to determine the colors and size of her final cloth. This stage is called aggan-ay. The net stage is called agpulipol, where the weaver rolls the thread up using a wooden spindle called a pulipol. This readies the warp threads for weaving. Next is the design setting phase or agpili, where the weaver inserts the horizontal weft threads into the base so she may start plotting the design. The final weaving process, agabel, uses a heddle bar (sikwan) that the weaver moves back and forth as her design slowly comes to fruition. The final woven products of Mang Cora and the Sabangan weavers are expertly crafted – a testament to their skill in mastering the tawid-tawid.

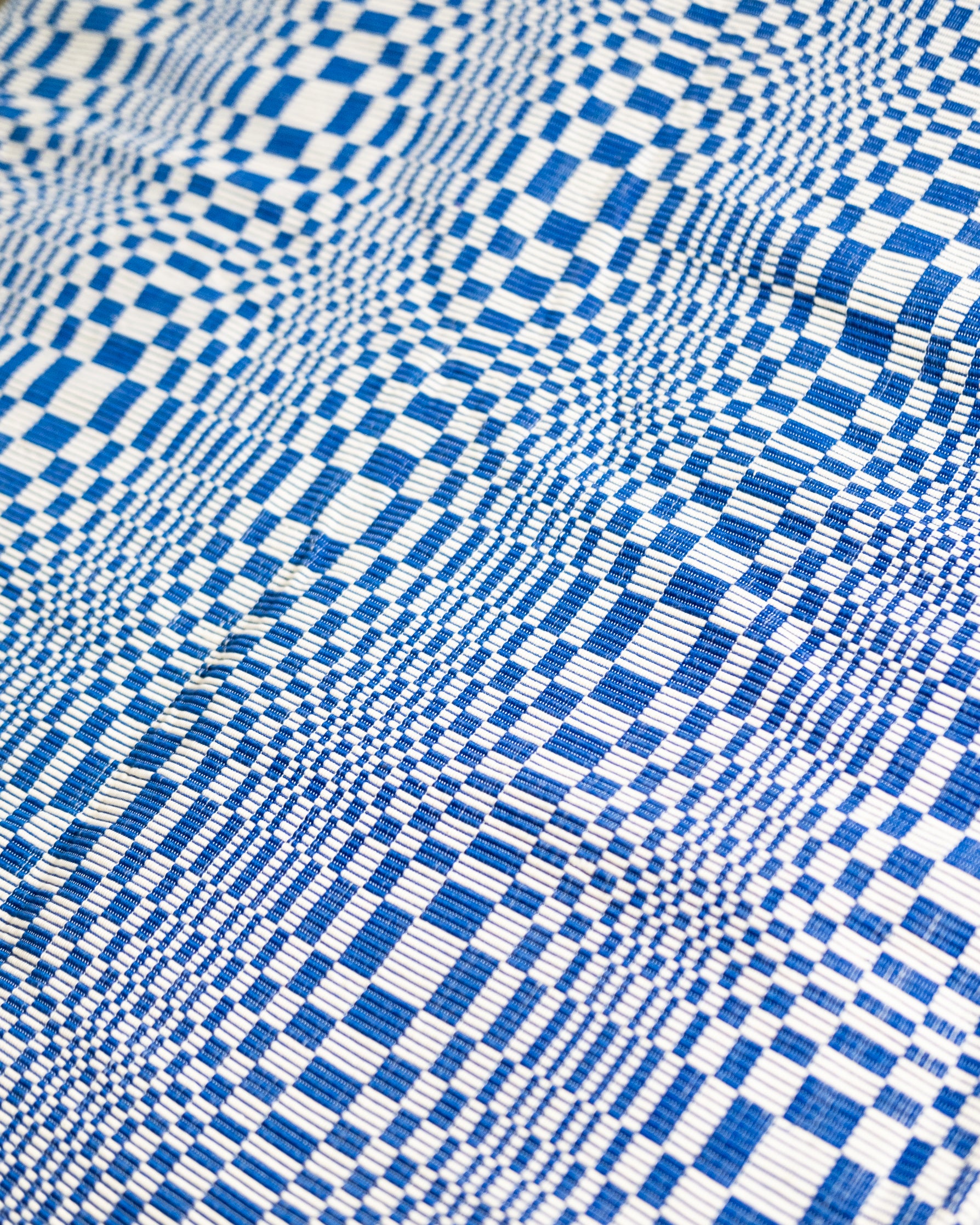

There are many known textiles that come from the weavers of Santiago. The most popular of which is known as inabel or the abel iloko. The Ilokano inabel is known for the geometric nature of its different variations. The accuracy of the grid designs, woven without any specialized equipment, shows just how precise the hand of an inabel weaver is.

A common pattern for many inabel cloths is the kusikus, characterized by undulating square grids meant to mimic whirlpool patterns. The weaving process that created the kusikus was known as binakol. Through sailors using kusikus cloths as masts for their ships, it was believed the patterns would appease the gods of the sea and protect them from whirpools. Another example of the inabel is the pinilian, which features a brocade weave, often with different colors of threads. The pinilian usually has different motifs woven into its warp, from human figures, or the tao-tao, to animals, to stars (sinanbaggak), and eye symbols (mata-mata).

Today, there is great appreciation for the Santiago inabel of Manang Cora and the Sabangan weavers. Both locally and globally, their weaves have become recognized for their beauty and skill. Supporting weavers and protecting the livelihoods of the weavers not only sustains their work, it nurtures art forms that have been practiced in the Philippines for generations.

Further reading:

Abel weaving:

https://www.vigan.ph/arts-and-crafts/abel-weaving-vigan-traditional-crafts.html

Pinilian and other weaves: https://www.tatlerasia.com/culture/arts/weaving-the-threads-of-filipino-heritage

Sabangan weavers:

http://car.da.gov.ph/2018/08/sabangan-weavers-association/