By Kayla De Leon

The Philippines is nestled in the heart of Southeast Asia, a bustling archipelago composed of more than 7,000 islands each with their own languages, cultures, and ways of life. But ask any Filipino what their last name is and you might be surprised at how un-Asian they sound like. After all, among the country’s most common surnames are de la Cruz, Garcia, and Reyes – names that wouldn’t be unusual in the streets of Spain.

The Filipino surname has always been a topic hotly discussed by the nation’s top academics. A whole slew of university theses have even been dedicated to studying and understanding how an entire nation was forced to change their names, adopting their identities from their oppressors and from a language that they did not speak.

Illustration from The Catálogo Alfabético De Apellidos

Historians largely agree that most pre-colonial Filipinos were named after their area of residence. For instance, someone who lived by the seashore would be called “Kato Tabing Dagat,” which directly translates to “beside the sea.” On the other hand, a native who resided in the depths of a forest would be named “Kato Ginubatan,” – the root word “gubat” means “forest” in English.

Some, on the other hand, had their names based on their father’s ancestry – sort of like a patronymic, if you will. For instance, the grandchild of a man named Tuliao would be called “Apo ni Tuliao.” In a similar vein, the daughter of Tasyo would be named “Anak ni Tasyo.”

Another popular practice was naming the person after a defining physical trait. This descriptive way of naming people is sometimes still seen today, albeit only as monikers and nicknames.

However, the pre-colonial ways of acquiring names all changed when the Spanish conquistadors came into the picture.

The expedition of the world-renowned explorer, Ferdinand Magellan, saw the discovery of the Philippines in 1521. What followed was over three centuries of subjugation, oppression, and forced assimilation. The Spanish colonizers exploited the country’s rich resources, filling the coffers of King Philip II, which helped usher in the Spanish Golden Age.

The pre-colonial Filipino identity was stripped even more in November 1849 when the appointed Governor-General, Narciso Clavería y Zaldúa – spurred by increasing complaints from the Regidor or Treasury Account – issued a decree that forced the natives to adopt Spanish surnames in a bid to make the census easier.

The Catálogo Alfabético De Apellidos

Madrid approved of the initiative and sent over a thick and heavy manuscript with the words “Catálogo alfabético de apellidos” emblazoned on its cover. The Alphabetical Catalogue of Surnames was quickly disseminated to the provincial governors who, helped by the town friars, instructed families to choose a name for themselves among the exhaustive list.

This initiative was enforced with severe and cruel penalties; in fact, the mother of the country’s national hero, Dr. Jose Rizal, was forced to traverse hundreds of miles on foot after she refused to use her assigned surname of Realonda.

Naturally, some of the less enthusiastic governors also implemented the program haphazardly and many provinces ended up with its entire population having surnames that began with the same first letter. For instance, the citizens of Miagao, a town located in the province of Iloilo, still all have surnames that begin with the letter “M.”

The book, as well as the words that it included, had also been hastily put together, which was why some natives ended up with embarrassing surnames like “utang,” which means “debt” and “teta” or “nipple.”

Despite the strict implementation of the program, some indigeous natives did manage to keep their pre-colonial and indigenous last names, which is why “Katigbak,” “Gatmaitan,” “Lakandula,” and the like still exist today.

Some say that these Filipinos had been excluded from the program as they had already been registered in the government’s books for committing crimes or misdemeanors. Others claim that these were the surnames of natives who had refused to live under Spanish rule, choosing to flee to the hills instead. Another popular theory is that these families had already been classified as pacified, baptized, and “civilized” taxpayers, which was why the local government units permitted them to retain their old names.

Still, the fact remains that most Filipinos today have Spanish last names – even if not a single drop of Spanish blood is present in their lineage.

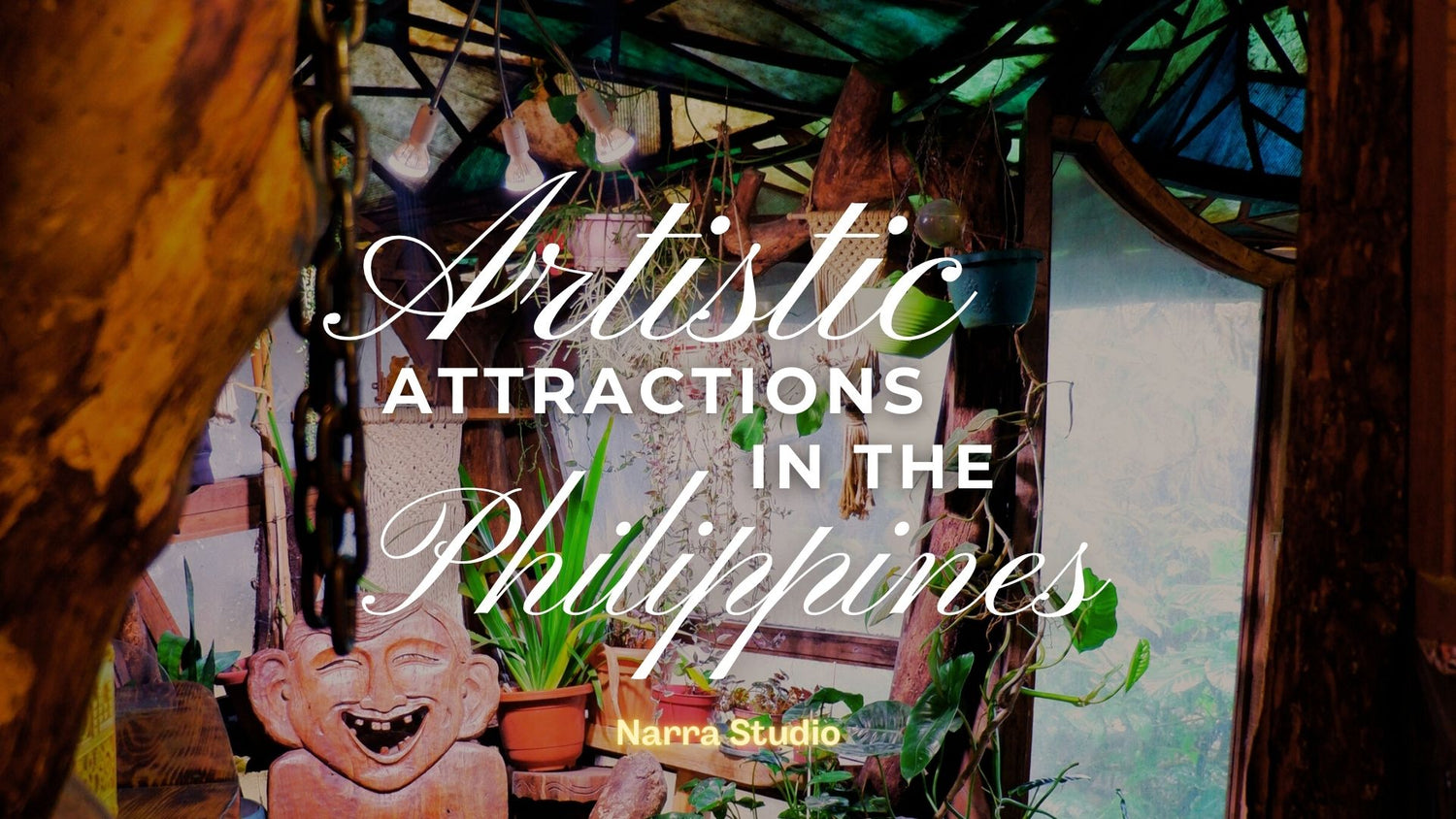

List of Spanish surnames from the book

It’s strange to imagine how the Philippines would have looked had the Catologo never been circulated. Perhaps then, Filipinos would boast of names that were more ancient, more authentic – names that spoke of both the tragedy and glory that their ancestors lived through.

View the original Catálogo Alfabético De Apellidos here at the Filipinas Heritage Library: https://issuu.com/filipinasheritagelibrary/docs/catalogo_alfabetico_de_apellidos?e=18015266/13622223